In 1988, one true crime story dominated the news cycle: The Billionaire Boys Club.

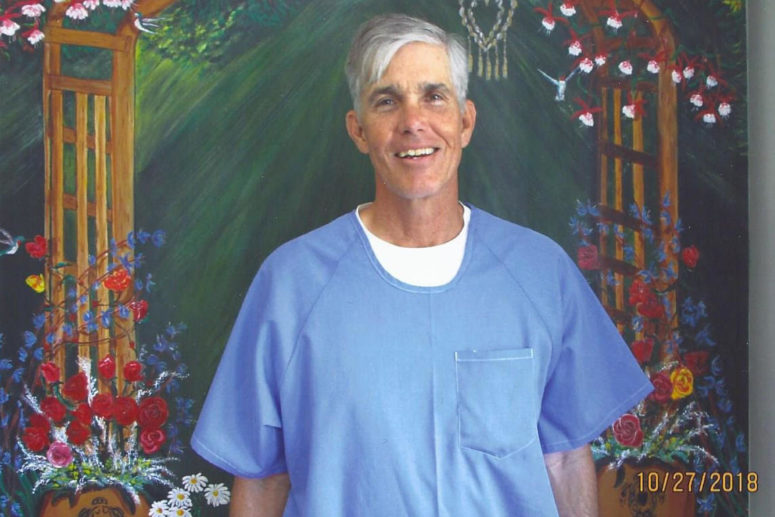

Three decades later, the story has faded from the tabloids, but it remains the painful present-day reality of club leader Joe Hunt, who remains in prison, serving a sentence of life without the possibility of parole for a murder he maintains that he did not commit.

Hunt readily admits to financial misdeeds. The 23-year-old Joe Hunt found himself in financial trouble from a fraud perpetrated on him by the master con artist Ron Levin, who bilked him out of a half million of his investors’ dollars, leaving Joe holding the bag. Joe naively overextended himself when he took Levin at his word that he would fund a large commodities investment intended to repay investors with a handsome profit. Instead, Levin assured Joe he could proceed with a purchase made with nonexistent funds. That’s when law enforcement got involved.

Soon after, Levin, who was out on bail and facing an FBI investigation for grand theft and fraud, went missing. In response to police inquiries, the rich kids of the Billionaire Boys Club directed attention away from themselves and pointed to Joe, the scholarship kid. Prosecutors decided to charge Joe with Levin’s murder, even with no body and no forensic evidence.

In addition to defending their client, Joe’s lawyers were burdened with the task of filing a judicial misconduct motion for mistrial after Judge Laurence Rittenband, well known as a “prosecutor’s judge,” slapped one member of the defense team with a gag order, leaving a workload meant to be divided among two lawyers to just one.

A Los Angeles Times article about the judge’s conduct explained that the mistrial motion raised charges that “Rittenband deliberately elicited prejudicial evidence against Hunt by questioning witnesses, that he belittled and banished defense staff from the courtroom, that he frequently refused to allow the defense to approach the bench to voice objections and that he aligned himself with the prosecution by grimacing, smirking and showing impatience and disbelief at crucial points in the defense’s cross-examination of witnesses.”

Ultimately, Hunt’s media notoriety (which extended to a fictionalized 1980s made-for-TV movie and a 2018 version of his story starring Kevin Spacey) worked against him in the trial, and he was sentenced to life without possibility of parole — which many observers characterized as an unjust sentence, especially in a murder case with no physical evidence — not even a body. Hunt’s sentence is an anomaly, not comparable to those of his fellow Boys Club members or even far more notorious criminals. For example, even the psychopathic cult leader Charles Manson was granted several opportunities to go before a parole board for his role in multiple murders. Yet Hunt has never been granted the right to a parole board hearing.

Grants of parole consideration are made not by guilt or innocence, but by an evaluation of an inmate’s rehabilitation, as well as an evaluation of any threat they may pose to public safety. Hunt hangs his hopes on a commutation petition that, if granted, would allow him to go before a parole board. Hunt, if given the opportunity, could make a strong case. His prison record is blemish-free, and his commutation application includes many letters of support, including letters from prison guards and chaplains.

“In my opinion, Hunt has no inclination to re-offend. All of his activities appear directed towards positive goals,” wrote a correctional officer from Pleasant Valley State Prison. “He has a reputation for helping others. I would place him solidly in the top one percent as far as suitability for reintegration with society.”

It’s testimonies like these — 47 in all are included with his petition — that form the last remaining basis for Hunt’s hope of release.

“I do hope that attention is drawn to the fight of people who have life without the possibility of parole,” Hunt said of the website his family has created to share information about his campaign for release, FreeJoeHunt.com.

Hunt explained that like himself, many of his fellow inmates who have been incarcerated since their youth have made profound changes by the time they reach middle age. “So I do hope that society as a whole becomes acquainted with this fact and they make room for the fact that the the work they have done is redemptive, and possibility invite them back to that role in society.”