“Billionaire Boys Club” Revisited

DAILY JOURNAL

Lawyer says backroom deal led to celebrated murder conviction for client 21 years ago

Nov. 21, 2008

By John Roemer

Daily Journal Staff Writer

Tales of the felonious preppies who ran the “Billionaire Boys Club” riveted Los Angeles in the 1980s and involved murder conspiracies, trials and convictions, two books and a TV movie.

The saga’s latest installment features the club’s imprisoned leader, Joe Hunt, who has a conspiracy theory of his own. An illicit backroom deal between a Los Angeles trial judge and a lawyer for Hunt should erase Hunt’s 1987 murder conviction and life-without-parole sentence and spring him from state prison, Hunt’s new lawyer contends.

A federal habeas corpus appeal ongoing in the Central District of California argues that the late Los Angeles County Superior Court Judge Laurence J. Rittenband drove a lawyer he disliked off Hunt’s defense team, depriving him of the right to counsel and fatally flawing his trial. Hunt v. Kernen, 98-5280.

State prosecutors defending Hunt’s conviction countered that a California appeal court has already authoritatively dismissed Hunt’s claims. Hunt’s attorney retorted that the state court’s reasoning is irreconcilable with the Constitution.

Hunt has been behind bars at the Sacramento-area prison formerly known as New Folsom since he was found guilty of first degree murder in the 1984 killing of Ron Levin, whose body has never been found. Levin allegedly embezzled millions of dollars from the “Billionaire Boys Club,” a group of youths from Los Angeles’ exclusive Harvard-Westlake School with extravagant spending habits who turned to crime to recoup investment losses.

Hunt has long claimed Levin framed him by faking his own death. The lawyer who wound up defending Hunt at trial failed to present several witnesses who claimed to have spotted Levin alive long after his asserted demise, the federal habeas petition states.

The state’s star witness against Hunt, Dean Karny, was a club member who testified against his former associates, entered a witness protection program and — under an unknown alias — became a California attorney licensed by the State Bar.

Hunt was accused in a separate 1988 trial in San Mateo County of murdering a second victim, Hedayat Eslaminia, the father of a club member. This time Hunt represented himself and, using witnesses his Los Angeles lawyer ignored, persuaded jurors to vote 8-4 in his favor. The hung jury made Hunt the only known California pro per defendant ever to have escaped the death penalty in a capital case. California appellate courts long ago affirmed Hunt’s Los Angeles conviction. His federal appeal gained fresh traction after Hunt, again acting as his own lawyer, filed successful pleadings to the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals to reverse a federal magistrate judge’s dismissal of his habeas petition, Hunt v. Pilar, 336 F.3rd 939 (2003). U.S. Magistrate Judge Arthur Nakazato of Santa Ana made procedural errors including issuing an unauthorized dismissal order, a unanimous three-judge appellate panel ruled. The decision returned the habeas petition to the district court, where Nakazato issued a final briefing order in June.

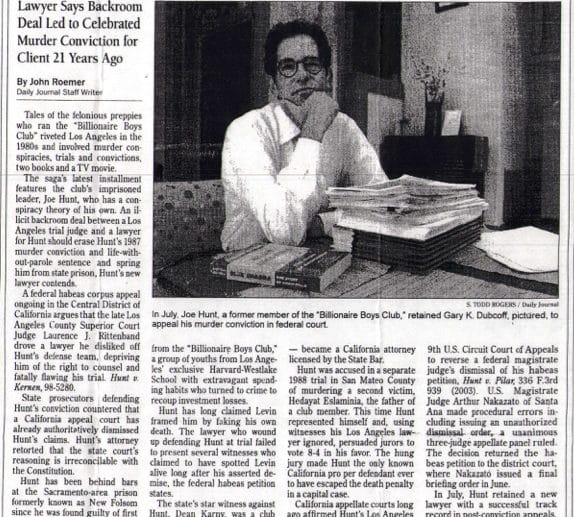

In July, Hunt retained a new lawyer with a successful track record in post-conviction appeals, San Francisco sole practitioner Gary K. Dubcoff.

Dubcoff refined, narrowed and sharpened Hunt’s arguments challenging his conviction.

Dubcoff’s pleading asserts that attorney Arthur Barens of Los Angeles agreed four days before Hunt’s 1987 trial that in exchange for Rittenband’s order he be paid from public funds to defend Hunt, he would not challenge Rittenband’s wish that his co-counsel not actively participate at trial.

Barens this week flatly denied claims in the pleading. “Truth and Mr. Hunt are strangers,” he said. “His arguments are false and untruthful, as lower courts have found. I zealously defended Mr. Hunt and I regret it didn’t end up successfully. Now, I’m sure Mr. Hunt will say anything in his desperation, and I can understand that.”

Rittenband died in 1993 after a lengthy career in which he sat on a number of celebrity cases. At a hearing for accused murderer Charles Manson, he demanded and got the defendant to drop his pose of facing away from the bench, according to published reports.

Rittenband also presided over the Roman Polanski rape trial and once vowed to retain his robe until the convicted defendant returned from France, where he fled to avoid sentencing, a vow the judge finally broke when he retired in 1989 with Polanski still overseas.

Prosecutors in the Hunt case at one point dubbed Hunt, “a yuppie Charles Manson.”

Barens’ co-counsel, Richard C. Chier, is also dead. Dubcoff said his research found several run-ins between Chier and the judge prior to the Hunt trial. They included a landlord-tenant dispute in which Chier was the tenant and Rittenband sought to intervene on the side of the landlord, a personal friend. The last straw came when Chier sought to disqualify Rittenband in the Hunt case.

“That sent him over the deep end,” Dubcoff said of the judge. “He told a deputy clerk to throw the disqualification motion in the trash.”

Then Rittenband allegedly maneuvered to exclude Chier from the defense. “Unbeknownst to Hunt, Barens had agreed to Chier’s silence in exchange for his own appointment … at public expense … after another judge had refused to appoint him,” wrote Dubcoff in Hunt’s appeal.

Under this arrangement, Barens was no longer an attorney within the meaning of the Sixth Amendment, Dubcoff wrote, adding, “He had already committed disbarment-grade acts, indeed felonies, to secure his public funding and had trashed, in the process, his supreme duty of fidelity.

“By agreeing to sacrifice his co-counsel on the altar of self-interest, he abandoned his client’s interests at this most critical stage.”

The judge, who had no legal authority to make such a funding order, committed reversible constitutional error in doing so, Dubcoff wrote. Rittenband and Barens met in the judge’s chambers with no court reporter present to reach their arrangement, Dubcoff wrote, citing material later placed on the record.

When the deal became public and the judge rescinded Chier’s appointment as co-counsel, a transcript shows that Chier asked in open court, “Does the client have anything to say about this, your honor?”

“No,” Rittenband replied.

Chier remained in court through most of the trial, but Rittenband ordered him not to speak, even in a whisper, to Hunt and Barens, the defense pleading states. The judge also steered the trial toward Hunt’s conviction, Dubcoff wrote. At one point Rittenband ordered his clerk to give a copy of the key piece of prosecution evidence against Hunt to each juror. That was a “to-do” list on which Hunt allegedly wrote step-by-step plans for Levin’s murder.

Even the prosecutor fretted that Hunt’s rights were at risk. Telling the judge he was “gravely concerned,” then-Deputy District Attorney Frederick Wapner — now a Los Angeles County Superior Court judge — objected on Hunt’s behalf, “I think that what is in the best interest of the defendant is not for the court to determine.”

Replied Rittenband, “I am running this trial, not you or they [the defense].”

Deputy Attorney General Elaine F. Tumonis of Los Angeles has advocated to uphold Hunt’s conviction for years.

“Our position is that [Hunt’s] federal constitutional rights weren’t violated and he’s only entitled to relief if he can show a violation of those rights,” Tumonis said this week.

Tumonis’ lengthy court document seeking to refute Hunt’s claims focuses extensively on the federal Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996. That law orders federal courts to give great deference to state court decisions unless the federal judges conclude the state courts acted unreasonably.

In the Hunt case, Tumonis argued, California appellate justices rejected Hunt’s claims either as unjustified or as harmless errors and that decision should stand.

Dubcoff thinks otherwise. “The attorney general doesn’t dispute our claims but just argues AEDPA, AEDPA, AEDPA,” Dubcoff said, using verbal shorthand for the federal law. “We believe the federal court won’t buy it.”

Dubcoff is a San Francisco sole practitioner with an uncommon record of attaining reversals for imprisoned clients. In one Marin County case, Dubcoff won a new trial, based on juror misconduct, for a man sentenced to life in prison over a drug slaying. Then Dubcoff descended from his appellate perch to represent the man in the courtroom at the second trial and persuaded jurors to acquit him.

He said he speaks with Hunt often via telephone. In one recent call Dubcoff quoted his client as saying, “As hellish as the last 20 years have been, I remain hopeful because I am now in federal court.”

Read More